This is the third and (maybe) the last part of a series of posts about sequential supervised learning applied to NLP. In this post I will talk about Conditional Random Fields (CRF), explain what was the main motivation behind the proposal of this model, and make a final comparison between Hidden Markov Models (HMM), Maximum Entropy Markov Models (MEMM) and CRF for sequence prediction.

You can find the first and second posts here:

CRFs were proposed roughly only a year after the Maximum Entropy Markov Model, basically by the same authors. Reading through the original paper that introduced Conditional Random Fields, one finds at the beginning of this sentence:

“The critical difference between CRF and MEMM is that the latter uses per-state exponential models for the conditional probabilities of next states given the current state, whereas CRF uses a single exponential model to determine the joint probability of the entire sequence of labels, given the observation sequence. Therefore, in CRF, the weights of different features in different states compete against each other.”

This means that in the MEMMs there is a model to compute the probability of the next state, given the current state and the observation. On the other hand, CRF computes all state transitions globally, in a single model.

The main motivation for this proposal is the so-called Label Bias Problem occurring in MEMM, which generates a bias towards states with few successor states.

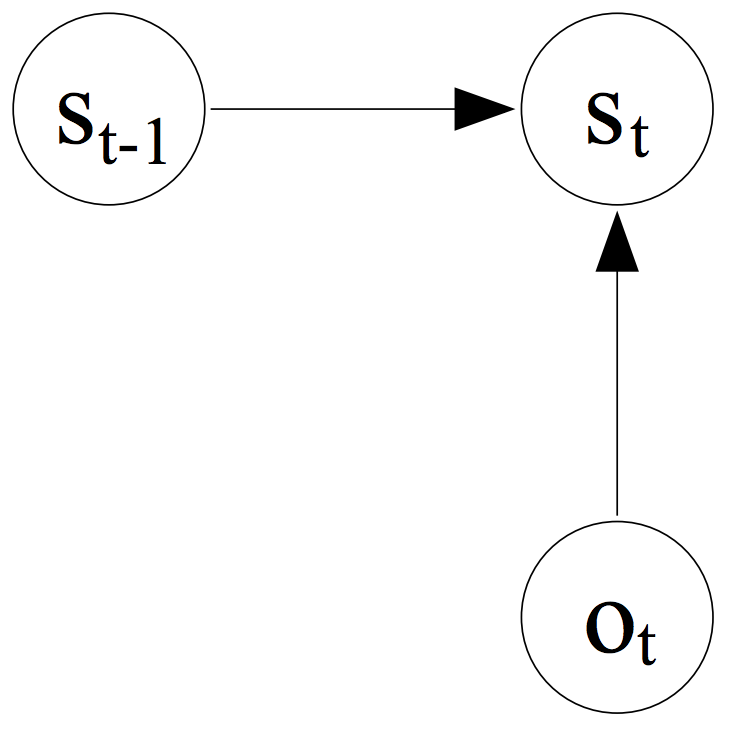

Recalling how the transition probabilities are computed in a MEMM model, from the previous post, we learned that the probability of the next state is only dependent on the observation (i.e., the sequence of words) and the previous state, that is, we have an exponential model for each state to tell us the conditional probability of the next states:

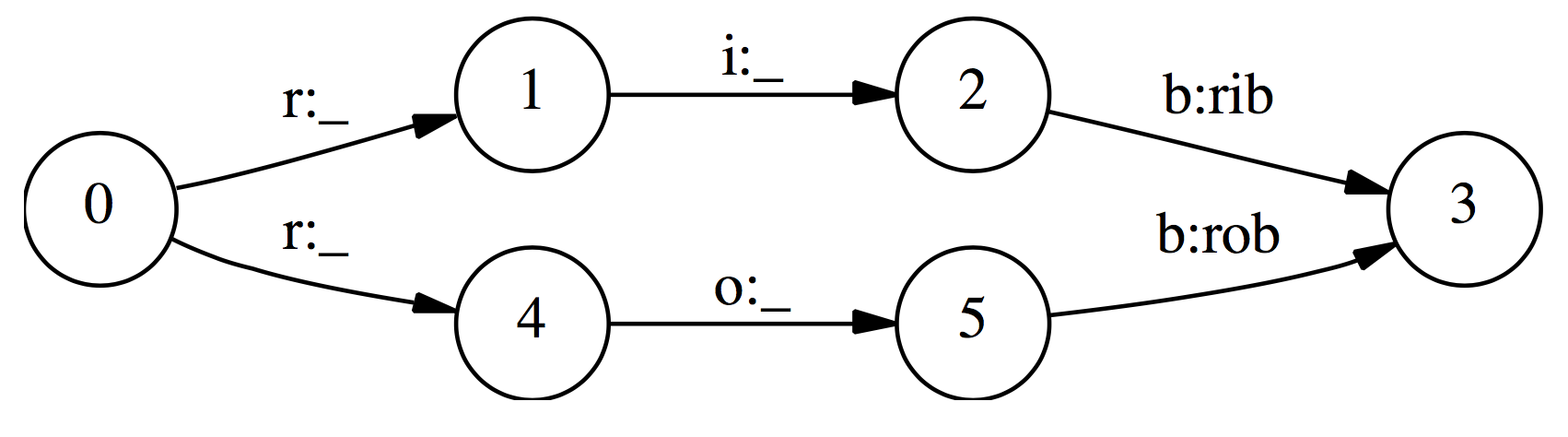

This causes the so-called Label Bias Problem, and Lafferty et al. 2001 demonstrate this through experiments and report it. I will not demonstrate it, but just give the basic intuition taken also from the paper:

Given the observation sequence: r i b

“In the first time step, r matches both transitions from the start state, so the probability mass gets distributed roughly equally among those two transitions. Next, we observe i. Both states 1 and 4 have only one outgoing transition. State 1 has seen this observation often in training, and state 4 has almost never seen this observation; but like state 1, state 4 has no choice but to pass all its mass to its single outgoing transition, since it is not generating the observation, only conditioning on it. Thus, states with a single outgoing transition effectively ignore their observations.”

“the top path and the bottom path will be about equally likely, independently of the observation sequence. If one of the two words is slightly more common in the training set, the transitions out of the start state will slightly prefer its corresponding transition, and that word’s state sequence will always win.”

The idea of CRF is to drop this local per-state normalization and replace it with a global per-sequence normalisation.

So, how do we formalise this global normalisation? I will try to explain it in the sections that follow.

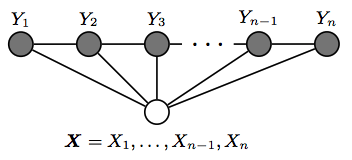

A Conditional Random Field can be seen as an undirected graphical model, or Markov Random Field, globally conditioned on \(X\), the random variable representing the observation sequence.

Lafferty et al. 2001 define a Conditional Random Field as:

Let \(G = (V , E)\) be a graph such that \(Y = (Y_)\ \ v \in V\), so that \(Y\) is indexed by the vertices of \(G\).

\((X, Y)\) is a conditional random field when each of the random variables \(Y_\), conditioned on \(X\), obey the Markov property with respect to the graph:

\[P(Y_ \mid X, Y_, w \neq v) = P(Y_ \mid X, Y_, w \sim v)\]

where \(w \sim v\) means that \(w\) and \(v\) are neighbours in G. Thus, a CRF is a random field globally conditioned on the observation \(X\). This goes already in the direction of what the MEMM doesn’t give us, states globally conditioned on the observation.

This graph may have an arbitrary structure as long as it represents the label sequences being modelled, this is also called general Conditional Random Fields.

However, the simplest and most common graph-structured in NLP, which is the one used to model sequences is the one in which the nodes corresponding to elements of \(Y\) form a simple first-order chain, as illustrated in the figure below:

This is also called linear-chain conditional random fields, which is the type of CRF on which the rest of this post will focus.

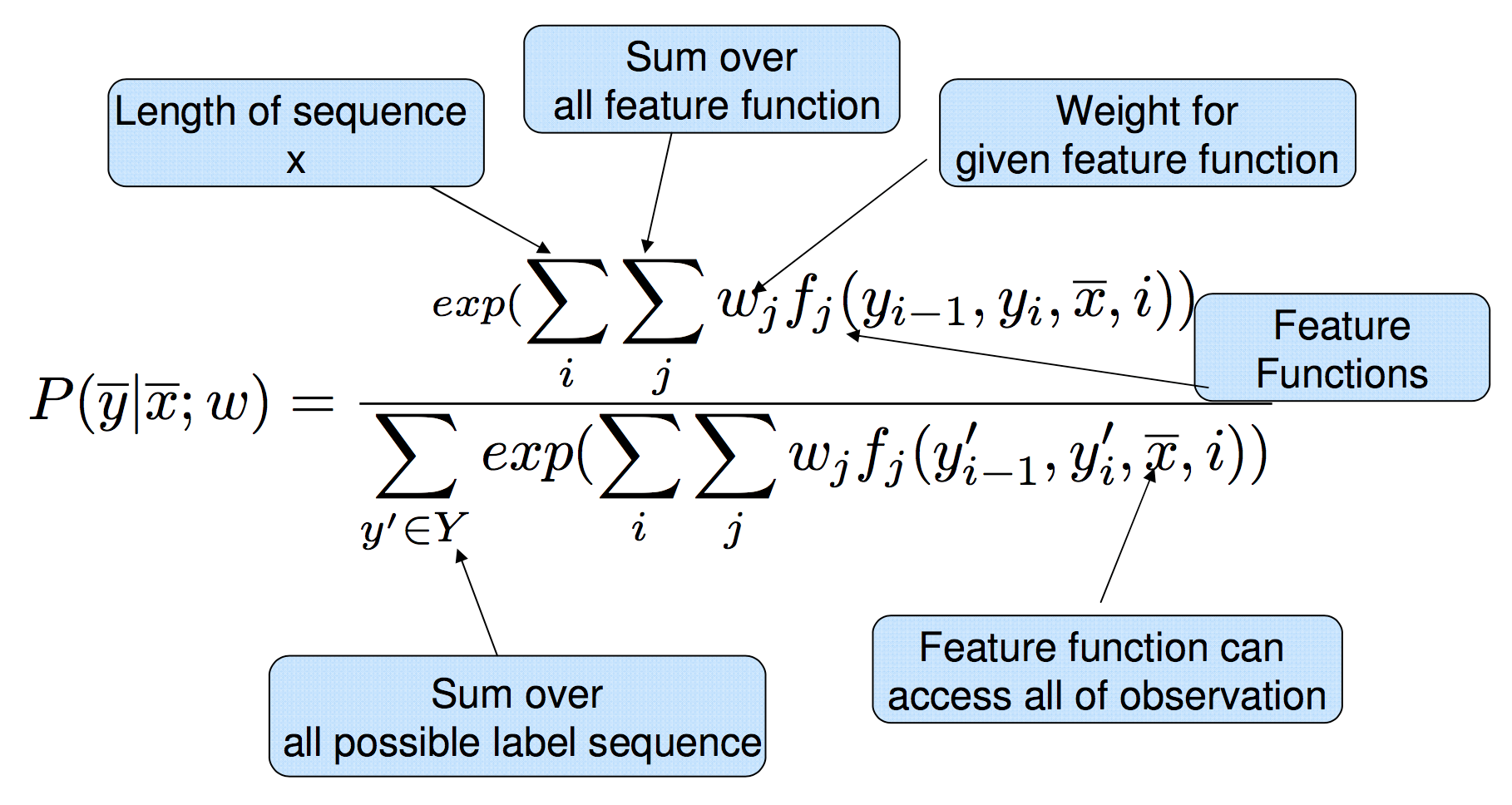

Let \(\bar\) is a sequence of words and \(\bar\) a corresponding sequence of \(n\) tags:

This can be seen as another log-linear model, but “giant” in the sense that:

\(F\) will represent a global feature vector defined by a set of feature functions \(f_. f_\), where each feature function \(f_\) can analyse the whole \(\bar\) sequence, the current \(y_\) and previous \(y_\) positions in the \(\bar\) labels sequence, and the current position \(i\) in the sentence:

\[F (\bar,\bar) = \sum\limits_ f(y_, y_, \bar, i)\]

we can define an arbitrary number of feature functions. The k’th global feature is then computed by summing the \(f_\) over all the \(n\) different state transitions \(\bar\). In this way, we have a “global” feature vector that maps the entire sequence: \(F(\bar, \bar) \in ^\).

Thus, the full expanded linear-chain CRF equation is:

Having the framework defined by the equation above we now analyse how to perform two operations: parameter estimation and sequence prediction.

Inference with a linear-chain CRF resolves to computing the \(\bar\) sequence that maximizes the following equation:

We want to try all possible \(\bar\) sequences computing for each one the probability of “fitting” the observation \(\bar\) with feature weights \(\bar\). If we just want the score for a particular labelling sequence \(\bar\), we can ignore the exponential inside the numerator and the denominator:

then, we replace \(F(\bar,\bar)\) by it’s definition:

Each transition from state \(y_\) to state \(y_\) has an associated score:

Since we took the \(\exp\) out, this score could be positive or negative, intuitively, this score will be relatively high if the state transition is plausible, and relatively low if this transition is implausible.

The decoding problem is then to find an entire sequence of states such that the sum of the transition scores is maximized. We can again solve this problem using a variant of the Viterbi algorithm, in a very similar way to the decoding algorithm for HMMs or MEMMs.

The denominator is also called the partition function:

is useful to compute a marginal probability. For example, this is useful for measuring the model’s confidence in its predicted labelling over a segment of input. This marginal probability can be computed efficiently using the forward-backward algorithm. See the references section for demonstrations of how this is achieved.

We also need to find the \(\bar\) parameters that best fit the training data, a given a set of labelled sentences:

where each pair \((\bar_, \bar_)\) is a sentence with the corresponding word labels annotated. To find the \(\bar\) parameters that best fit the data we need to maximize the conditional likelihood of the training data:

the parameter estimates are computed as:

where \(\frac<\lambda> \| \bar \| ^\) is an L2 regularization term.

The standard approach to finding \(\bar^*\) is to compute the gradient of the objective function and use the gradient in an optimization algorithm like L-BFGS.

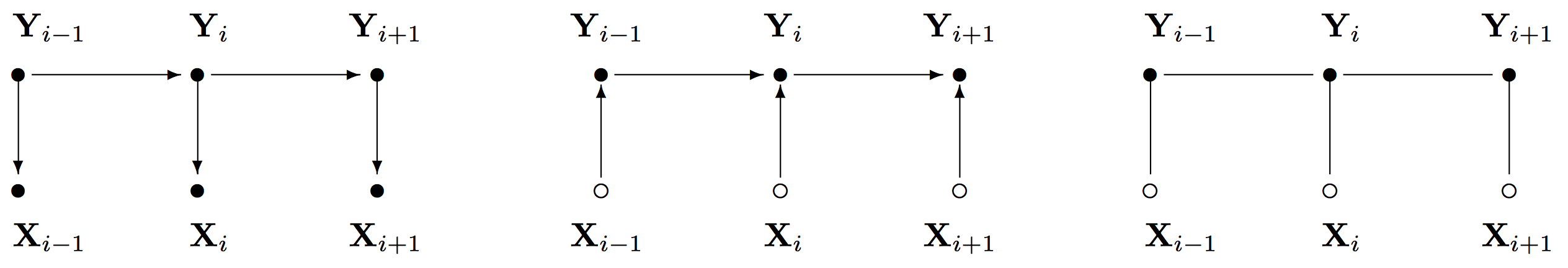

It is now helpful to look at the three sequence prediction models and compared them. The figure below shows the graphical representation of the Hidden Markov Model, the Maximum Entropy Markov Model and the Conditional Random Fields.

The writing of this post is also the outcome of many discussions and white board sessions I had together with Tobias Sterbak and Sebastian Mika.