What are some of the most common types of questions for teaching critical thinking? This led to many dozens of answers.

by Terry Heick What are the different types of questions? Turns out, it’s pretty limitless. I’ve always been interested in them–the way they can cause (or stop) thinking; the nature of inquiry and reason; the way they can facilitate and deepen a conversation; the way they can reveal understanding (or lack thereof); the stunning power of the right question at the right time. There’s a kind of humility to questions. Someone who doesn’t know asks someone who might. Or even someone who does know (rhetorically) asks someone who doesn’t to produce an effect (rhetorically). There’s a relative intimacy between someone asking and answering questions, one that says, ‘We need one another.’ It’s from that kind of perspective that TeachThought was founded, so it was surprising to me when I realized recently that, after years of writing about questions and questions stems and the power of questions and so on, I hadn’t ever written about the types of questions. After doing some research, I realized that identifying clearly what the ‘types of questions’ are isn’t easy because there isn’t a set number. Much like when I wrote about types of transfer of learning or types of blended learning, it was clear that although I kept seeing the same categories and question types, there really wasn’t a limit. When I asked myself, ‘What are the different kinds of questions?’ I was asking the wrong question. A slight adjustment: What are some of the most common types of questions? What are the categories of questions? What are the most common forms of questions? This led to many dozens of answers. There are dozens of types of questions and categories of questions and forms of questions and on and on and on. An entire book could be written about the topic (if not a series of books). But we have to start somewhere, so below I’ve started that kind of process with a collection of types of questions for teaching critical thinking–a collection that really needs better organizing and clearer formatting. Hopefully I can get to that soon. Let’s start out with some simple ones.

Multiple-choice/Single: A question with multiple available answers for the responder to choose from but only one correct solution Multiple-Choice/Multiple: A question with multiple available answers for the responder to choose from and more than one correct solution See The Problem With Multiple-Choice Questions True-or-false: A statement that the responder must decide is ‘true’ or ‘false’ Fill in the blank: A statement with a key piece of information missing that the responder must add to make the statement complete and true Matching: Most commonly, Matching Questions have two columns and each column has items categorized by a clear rule that must be matched to items on the opposing column. For example, the column on the left can have words and the column on the right can have definitions. Other possibilities: Left Column/Right Column: Inventors/Inventions; Forms of Government/Strengths and Weaknesses, Geometric Shape/Formula to calculate area; etc. A variation of the Matching Question has one column holding more items than the other. This generally makes the question more complex–or at least more difficult–as the responder can’t be sure all items are used and must be more selective. Deductive reasoning (process of elimination, for example) is less accessible to the responder. Short-Answer: This is less close-ended than the above common assessment questions types. In a short answer, the responder must answer the prompt without the benefit of any additional information or possible answers. Analogies: These aren’t exactly a type of ‘question’ but analogies excellent assessment tools and can be used in many of the other forms of questions–multiple-choice for example. Pig : Mud :: Bird: _____ (simple) Pig: Mud :: Mitochondria: ___ (less simple)

This one isn’t simple or standardized either. There are simply too many different ways to think about inquiry. You could, for example, use every level of Bloom’s Taxonomy and say that there are ‘Evaluation-level questions’ and ‘Analyze-level’ questions and ‘Remember’ and so on. A lot of this comes down to function: as a teacher, what are you wanting the question to ‘do’? With that in mind, let’s look at just a few examples (this is by no means an exhaustive list). The Definition of Factual Questions: Questions with unambiguous, more or less universally accepted objective answers based on knowledge. The Definition of Interpretive Questions: Questions meant to interpret something else–a comment, work of art, speech, poem, etc. The emphasis here is on the thinking process and will often result in an improved understanding of that ‘other’ (rather than demonstrating knowledge as is the case in a Factual Question. Responses to Interpretive Questions should be evidence-based but are inherently subjective, open-ended, and ongoing. The Definition of Evaluative Questions: Questions that emphasize one’s personal opinion–of the value of a law or the strength of an author’s thematic development, for example. Analytical Questioning and Didactic Questioning are common forms of questioning and inquiry whose role is simple and whose patterns are clear and plain enough to see and follow. The Definition Of Analytical Questions: Questions meant to understand–to identify the ‘parts’ and understand how those parts work together and depend on and affect one another. Analytical Questions depend on other higher-level thinking skills like classifying, attributing, and organizing by rules or other phenomena. An example of an Analytical Question might be to ask a student about character motivation in a novel or how science drives technology–“What is the protagonist’s motivation in the story and how do we know?” or ‘Why was this event important?’. The Definition Of Didactic Questions: Structured, formal questions commonly about facts and knowledge at the recall and comprehension level, including remembering, describing, explaining, naming, identifying, etc. Examples Of Didactic Questions: ‘Who, what, where and when’ can be examples of Didactic Questions while ‘Why’ tends more toward an Analytic Questions (see below).

The Socrative Method is among the most well-known version of the Didactic approach, where students are (or can be, depending on how the seminar is structured) guided by ‘more knowledge others’ (MKO) personalized and extended reflection through inquiry. This, of course, can result in the thinker shedding their own dogma and reaching enlightenment. It’s not very scalable in a classroom with one teacher and 34 students, which is where the Socrative Seminar comes in–a ‘built-for-the-classroom structure to bring learning-through-questioning’ into traditional educational spaces. This Socrative Seminar (or ‘Method’) is a formal approach to inquiry-based conversation where open-ended questions are used to facilitate discussion by students who respond to prompting from the teacher or comments and questions from other students. It’s not exactly a ‘type of question’ but is a format to use questions to promote understanding in a classroom. This method is dialectical and dialogic, depending on the ability of students and teachers to be able to verbalize often complex and abstract thinking. A ‘good’ question in a Socrative Seminar would be much different than a ‘good’ question on a criterion-referenced assessment. What is a ‘good question’? The quality of a question, then, is highly contextual–and to answer it with any clarity, you have to be able to answer: For that student in that situation at that time, what did that question do? What was the effect of that question? See also ‘The Relationship Between Quality And Effect.’

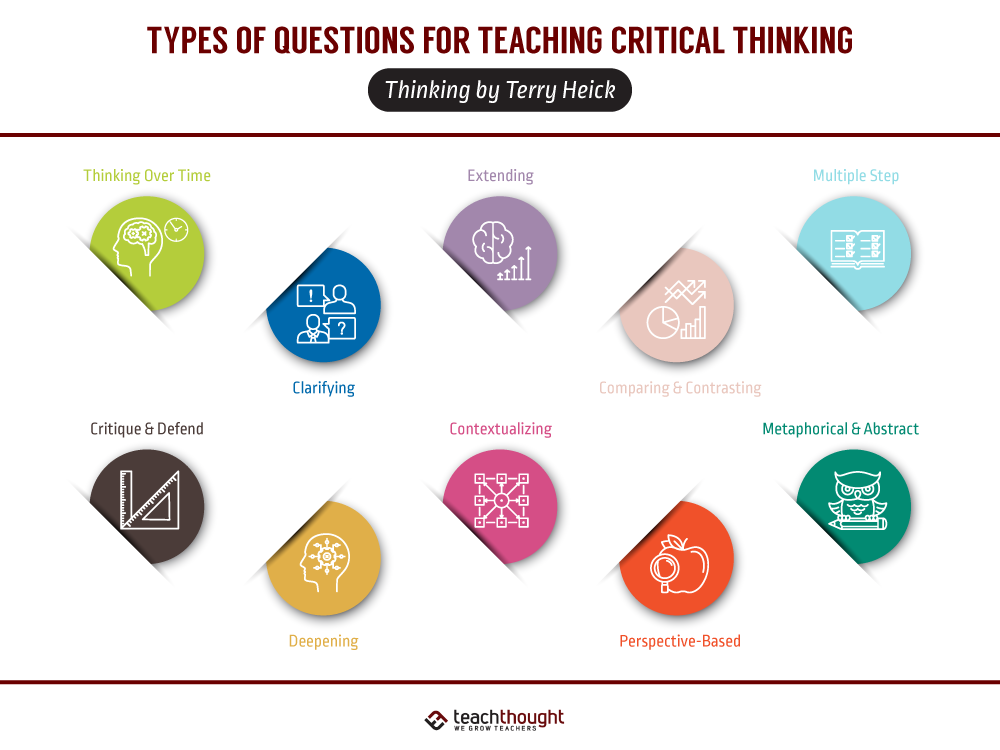

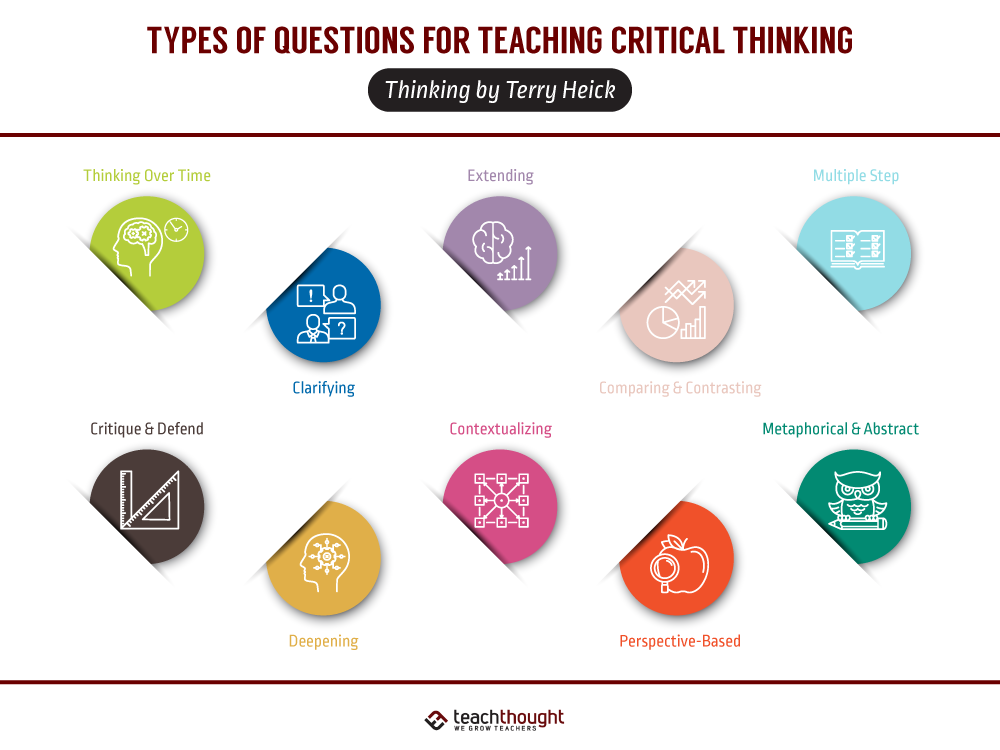

Clarifying Question: A question meant to clarify something–either a question asked by the teacher to clarify the answer a student gives or what the student thinks or a question asked by the student to the teacher to clarify something (a statement, a task, a question, etc.) Probing Questions: A probing question does what it sounds like it might: Serves as an inquiry tool to explore a topic or a student’s thinking and existing understanding of a topic. Probing questions also have different forms, including Emphasizing, Clarifying, Redirecting, Evaluative, Prompting, and Critical Analysis. Thinking Over Time Questions: Questions that reflect on an idea, topic, or even question over time. This can emphasize change over time and lead to cause/effect discussions about the changes. This can also focus on metacognition–one’s thinking over time and how it has changed, etc. Extending Questions: Questions meant to continue to lead a discussion, assessment, or ‘learning event,’ often after a ‘successful’ event immediately prior. For example, if a student is asked a question about adding fractions and they answer successfully, the teacher can ask an ‘Extending Question’ about adding mixed numbers or decimals. Deepening Questions: Similar to Extending Questions, a Deepening Question increases in complexity rather simply extending what’s been learned. In the scenario above, after answering the question about adding fractions, a teacher could ask how exponents or the order of operations might affect adding fractions. Transfer Questions: Questions meant to ‘laterally’ extend an idea without necessarily becoming more complex. If discussing the orbit of Saturn, you could ask an ‘Extending Question’ meant to take knowledge gleaned from that discussion and apply it Contextualizing Questions: Questions meant to clarify the context of a topic/question/answer rather than to elicit an ‘answer.’ Perspective-Based Questions: Questions focused on the effect perspectives have on answers and/or ‘truth.’ Perspective Questions can also be asked from specific points-of-view–a student could answer a question about government from the perspective of a modern citizen, citizen of an ancient culture, famous historical figure, specific political party, etc. Concrete Questions: Usually a ‘close-ended’ question, Concrete Questions ask students to provide ‘concrete’ answers–names, quantities, formulas, facts, characteristics, etc. See the following item for an example. Metaphorical & Abstract Questions: The opposite of Concrete Questions, Abstract Questions intended to draw attention to or more closely understand abstract ideas or the abstraction in non-abstract ideas. These can also be thought of as Thematic or Conceptual Questions. For example, asking a student to identify the three branches of the US government would be a ‘Concrete Question’ while asking them to describe, from their perspective, the virtues of democracy or how ‘freedom’ affects citizenship are examples of Perspective-Based Abstract Questions. Compare & Contrast Questions: Questions that–you guessed it–ask students to identify the way two or more ‘things’ (concrete or abstract, for example) are the same and different. Claim/Critique & Defend Questions: Questions (or prompts) that ask students to make a claim or issue a ‘criticism’ (e.g., of an argument), then defend that claim or criticism with concrete evidence. Cause & Effect Questions: Another more or less self-explanatory category, Cause & Effect Questions require students to separate cause from effect or focus on mostly causes or mostly effects. These can be Concrete or Abstract, or Perspective-Based as well. Open-Ended Questions: Often subjective questions meant to promote conversation, inquiry, etc. Open/Open-ended questions are central to Socrative Dialogue (though closed/yes or no questions can be just as effective at times because questioning is an art). Closed Questions: Questions with yes or no answers generally used to check for understanding, emphasize an idea, or uncover information Leading Questions: Questions meant to ‘lead’ the thinking of the responder in a specific direction for an intellectual or psychological effect Loaded Questions: Questions embedded with an underlying assumption–one that might contain faulty reasoning, bias, etc. This question is characterized by those faulty or otherwise distracting assumptions rather than the assessment or answer. Dichotomous Question: A type of Closed Question with only two answers (generally Yes/No) Display Questions (Known Information Question): A way to check for understanding; a type of question that requires the answerer to ‘perform’ or demonstrate their understanding by answering a question the questioner already knows the answer to. Then there are Referential Questions: An inherently subjective question, Referential Questions produce new information and can be either open or closed-ended questions. An Example of a Referential Question: Which character in Macbeth would be most likely to be a successful YouTuber (or ‘streamer’) today? Rhetorical Questions: A question asked to create some form of effect rather than produce an answer. These are useful in discussions but can also be used in writing as well. After all, who is going to answer a question posed by an author in an essay? Epistemic Questions: Questions about the nature of knowledge and understanding. This is more of a content-based category rather than a universal ‘type of question,’ though asking students about the nature of knowledge in math or science–how we form it, how we know if it’s accurate, the value of that knowledge, etc.–can be used in most content areas. Divergent Questions: According to Wikipedia, a divergent question is a “question with no specific answer, but rather exercises one’s ability to think broadly about a certain topic.” Inductive Questions: Questions meant to cause or induce the responder to form general principles theories based on observation, evidence, or data. In inductive reasoning, the conclusion or argument becomes more general than the premises that prompted it. Deductive Questions: Questions meant to support the responder in forming a the given theory based on continued testing. In deductive reasoning, the conclusions drawn are less general (i.e., more specific) than the premises given and in a valid deductive line of reasoning, the conclusion must be true if the premises are true. 5 Ws Questions: Wonderfully simple and devastatingly effective questions: Who, What, Where, Why, and When? And you can add ‘How’ to the list, too. These include Who, What, and Where questions? These can be useful in guided discussion, reflection prompts, the formation of essential questions, and more.

What’s the point? What’s the big idea? What’s the purpose? What is the process? What’s more important here? Less important? What crucial information are we missing? What did they think or believe and how did that belief change over time? What contributed to that change? Why should I learn this? What should I do with what I’ve learned? What is the author, speaker, write, or artist ‘saying’ here? What are they underlying assumptions of that message? What is the author’s point of view? What do I believe and how does that affect what I think others believe–or how does it affect what I think about what they do believe? What should I ask about this? How can I improve the questions I or others have already asked? Is the answer wrong or is the question ‘wrong’? Education Expert